I met Ethan when we were artist mentors together at Southern Exposure in 2015. Since then I have watched his practice grow into the world in a way that I find really exciting and that I really relate to. So I asked him if he would let us explore his practice a little bit here. – Eliza Gregory, May 10, 2017

Where do you locate the most meaningful part of your practice right now?

Tricky one, you are catching me in a lull. I am sure I would have said Touring and Performing just two months ago. It’s probably still Touring and Performing. It’s just winter, I am in Norway as I write this, and I’m sewing new books and pondering ways to gas-light the president.

How has your relationship with your audience changed as you’ve done the Shock and Awe Book Tour?

How has your relationship with your audience changed as you’ve done the Shock and Awe Book Tour?

I have tried to respond to this question so many times, and failed. I just swallowed back thousands of words about the election.

To be succinct: before the Tour, my audience was my community. After the Tour, my audience still feels like my community. For a while—in the middle—things got nuts, and the scale reached the point where I stopped remembering faces, names, which was painful (and sometimes embarrassing). I always wanted this project to do one thing: bring Author, Subject, and Viewer onto a level playing field. But scale and jumping into different cultures changes things.

Before the Tour, I was the product of a community. I have been lucky to have a groundswell of middle-class patrons. Sometimes it’s not there, but usually it is. On a long enough timeline the continuity remains—I’m the product of a very wide, dedicated community.

Before the Tour, I was the product of a community. I have been lucky to have a groundswell of middle-class patrons. Sometimes it’s not there, but usually it is. On a long enough timeline the continuity remains—I’m the product of a very wide, dedicated community.

Before the Tour, the audience was a bit stuck in this role of receiving, supporting. Inside the Tour, collaborations grew, sometimes out of nowhere. Secondary works, inspired works, whatever you want to call them—a lot happened. Have you heard Lia Rose’s song? This is probably the most famous.

But every night—100 performances—I can recall the magic moment—the moment it left my hands and began to grow. Sometimes it burned-off fast, but generally it stuck around for a while. I recall in Oxford, this American woman said, “it feels like you’re inhabiting my memories, it’s like they are my memories, but they aren’t…” This was when it went really well—the point of the expanded-author is to expand space for others, in this case to allow the process of the narrator reclaiming their memories from trauma to function for others. When it worked, the audience explored their own memories, histories. Reclaimed, for themselves. And with some gentle help, somewarmth—to recite, for others. The period since 2001 is not History yet. I fear the day that it is. It’s always seemed like a wave, coming to wash us all away. And then the fortress of Memory—it’s always falling.

It’s hard for me to know where things stand with my audience now, and going forward. I am curious to see where things go—some folks came to the Tour 2 or 3 times. I’m sure we aren’t done working together. But then, the audience was so wide, particular to this passage in history—I’m not sure these folks are the same folks showing up for future projects. Time will tell what is necessary.

Which part of Shock and Awe gets people the most jazzed/excited/engaged? What’s been some of the feedback (both positive and negative) that you’ve gotten as you’ve gone along through the touring and performing?

Which part of Shock and Awe gets people the most jazzed/excited/engaged? What’s been some of the feedback (both positive and negative) that you’ve gotten as you’ve gone along through the touring and performing?

I think it’s all about the oral tradition. Maybe it’s the constant digital, the constant edit—but the dude in the front of the room, reading, telling stories, weaving threads—it just works. I’ve been told that it feels “completed,” and I think that’s the right word. Some nights it’s just a thick magnetic glue. It’s a total engagement, it goes both ways.

The feedback has mostly been positive. In Art Land, the process has made me a curiosity with institutions—for better and worse!—who often ask for meetings and then have no idea what to do with me (HINT: give me two hours, a stage or a room filled with chairs, and tell all your friends tobring their favorite fork). But really, at the end of the day, I found a way to bring the project to tens of thousands of people, and there are too many wonderful moments to count. Just a few ugly moments, most of which were pure misunderstanding (except the time white supremacists showed up…). Also, in case I don’t mention this anywhere—it’s important to remember that this embrace didn’t just come from an art crowd. The events drew a very wide slice of American life. And then Europe, too. My rule was to do every event possible, whomever wanted to host, whatever the location.

Can I offer negative feedback on my own project? If I can, I note that the project had limits in the US that I did not experience in Europe. In Europe I was a public intellectual. The ideas were allowed to grow. I presented the project in the most prestigious social science and public policy spaces in Europe and the UK. The intense research behind the project mattered.

Can I offer negative feedback on my own project? If I can, I note that the project had limits in the US that I did not experience in Europe. In Europe I was a public intellectual. The ideas were allowed to grow. I presented the project in the most prestigious social science and public policy spaces in Europe and the UK. The intense research behind the project mattered.

In early 2016, during a Q-and-A after an event in the US, I was asked who I thought would win the election. I told the crowd I thought it was Bernie or Trump, to take fascism seriously. They laughed. A close friend told me I “wouldn’t be taken seriously without data.” Crossing the United States 100 times was not deemed “data.” Sharing Shock and Awe 50 times—with 50 different communities sharing their experiences—was not research. I traveled to 45 states in 2015, it was so clear to me Trump would win. I couldn’t convince anyone in liberal, wealthy coastal enclaves to take this seriously. People wanted to look at polls in the NYTimes. And they’ve been told their whole lives Art is Bullshit. Looking back on it—to say the least—I feel that being an Artist in the United States comes with serious restraints. It’s an ecosystem-wide problem.

How did your arts education prepare and fail to prepare you for this kind of practice?

I studied at a time when Social Practice was not yet a thing. Social Sculpture was a thing. Performance, everything that came after sculpture in the expanded field—all of this was huge for me. But I was making photographs. It was very schizophrenic.

There’s no nice way to say it. Too often Photography—as pedagogy—entirely ignores the History of Art. Or just sort of touches down on the history of painting, cinema, and we get lame Yale shit. It’s just weak. In my 20s I visited Graduate programs, and ultimately decided against this path. I saw this pattern—I guess it’s just myopia.

My formal education happened at the end of the story of public funding, NEA grants—we were told we could be Foundation Artists, teach, etc. This story just died so hard for me with the recession. In one sense I felt I had no preparationfor Capitalism. This doesn’t mean, “the real world,” or some lame Republican sentimental-horse shit. I am speaking about the savagery of the recession—the hunger, homelessness, poverty, and—ultimately—death that inflicted my community. Universities, and art schools in particular—they are certainly blowing it with the story of the 1% artist. But the structural failures in the system are bigger than this.

Touring and performing happened as a response to the way the arts changed after the Recession. To say it bluntly, I note that the stated reasons many Americans don’t care about—nor respect—Artists is precisely what we say, privately, about the institutions, and the career-liberals peddling the non-sense that comes with privatization. The Big Lebowski has a caricature of this. Anyway, I was always getting out. I needed to find a way to get my work back to the community. There was just no way to bring the subject and audience into cooperation within the options available to me. And then I noted that my only friends ‘working’ were musicians.

One final note here—I left art school to study at Reed College. This was an insane experience, I realize now. Essentially, we did masters theses in our final year. I was surrounded by wild minds and had an advisor—Gerri Ondrizek—who pushed us as far out of the gallery and white cube model as could have been done. I am sure she would have failed us if we had made anything meant for a gallery. Huge tip of the hat to her.

How has your understanding of photography and how it functions changed as a result of this new way of working? What is the role of fine art photography in the 21st century?

This project came about as the Art World went ape shit for Process-based Abstraction, Materials-based Abstraction, whatever you want to call it. I will state on record that I think this swing had political motivations—bad ones—and that someday we will find out how, and why, this happened. To be clear: I do not buy it. Everything Camille Paglia said about Gloria Steinem in the 70s—that’s my comment on the ascendancy of Process-Based Abstraction. Same shit with Pollock, the Paris Review, etc.

Also to be clear: I have curated shows of this work, and support many artists who work through these processes. But the swing that occurred was too large, and the timing is impossible. And it’s happened before. The 1970s and the post-08 Recession period are not supposed to be marked by a swing toward an apolitical—out-of-the-world—approach to the medium. This is of course swinging hard right now, or so the rhetoric would suggest, as Trump carries on with his total nonsense.

Prior to touring, I had the sense that Photography had devolved into fundamentalist camps. There were those still in the world, via Photojournalism, and the Documentary mode—just still carrying on with the same old thing. After Trump I heard a famous photojournalist remark that the problem was—still!—that people weren’t forced to look. No critical reflection on the medium, the methods, the role and place of the audience. And then Art Photography—more or less this seemed to have become Materials and Process.

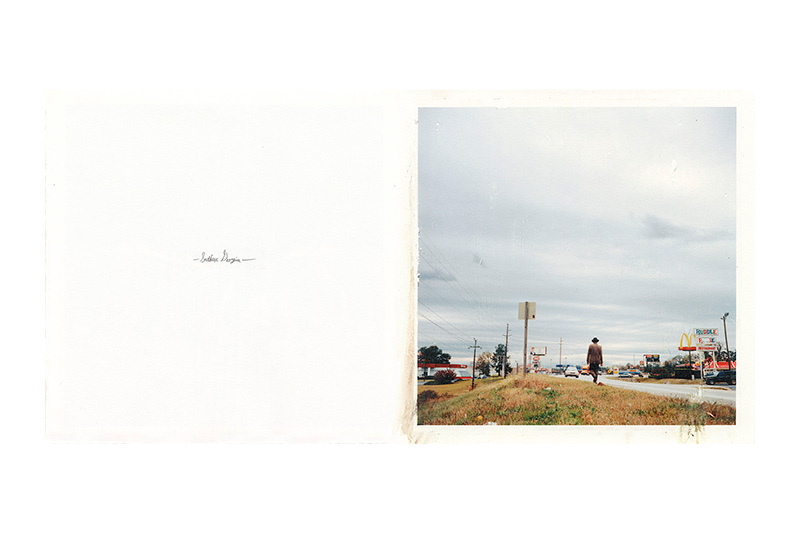

In a way, I saw what I was doing as making a space for a kind of Folk Photography. I fell in love with Folk Art along the way. For me, greatFolk Art has the critical capacity and self-awareness or Art, but carries subjectivity in a different way—like the death of the author came early. And I noted, too, that often the results were treasured, both for their materiality and their ideas. I wanted to make a kind of mennonite-rug-wrapped Harmony Korine film, blur Indy and Folk. Cast-iron pie and all.

In a way, I saw what I was doing as making a space for a kind of Folk Photography. I fell in love with Folk Art along the way. For me, greatFolk Art has the critical capacity and self-awareness or Art, but carries subjectivity in a different way—like the death of the author came early. And I noted, too, that often the results were treasured, both for their materiality and their ideas. I wanted to make a kind of mennonite-rug-wrapped Harmony Korine film, blur Indy and Folk. Cast-iron pie and all.

Part of what I was doing was using the populism of the medium. If you’re going to make Art with photographs, you may as well bring the world into it. In the 21st century, it’s imperative that we make photography a Folk Medium. It’s within our reach. Artists can still run experiments, I’m not excluding any kind of practice. But at base, there was something wrong with the reign of Fine Art Documentary, and now Process Based Abstraction. And it’s not enough just to say that populism in Photography is rooted in free-market Kodak marketing. There’s another level here.

I ‘m pretty darn excited about everything you are saying. I would add that when you are making work with images in the 21st century, you can no longer pretend that it’s difficult to make images. Sure, some images are difficult to make. Art that is meaningful is difficult to make. Some images are better than others. But really most people can make a good picture, and do make them very often. So just being focused on making a good image is not enough to make you an artist. You really have to be thinking about how you make the picture, why you make the picture, who sees it, how it functions, and what its impact is on the world.

I totally agree. The ease of image making has made the container unavoidable — physical, social, whatever it may be. And there’s some really weird shit to work with from this place. Like, why are we still looking at the same 10 images of Africa? Why are bylines still from the same 3 places for a whole continent? I used to make work in this region, 10 years ago — I am blown away that the mass media representation hasn’t changed at all.

There is another thing I’m pondering, too, maybe another interview — the photograph vs. the image. It may be a sentimental distinction for some, but for me I make photographs, not images. I make images knowing how I will print. Compensating for this. It’s a graphic art. Image making has gone in other directions, which I respect, admire (Hito Steyrel comes to mind). But ultimately this isn’t what I’m doing. I’m a bit of a modernist — I care about ink, paper, and making sure my friends feel high as hell when they stand in an installation or chill with my books.

What are you working on next? How has this tour influenced things you are beginning now?

Everything I envision has a touring and performing component. I guess that’s a big result of the process! The NEA has not been cut, but it’s at the same miniscule level in comparison to arts funding in Europe and the Commonwealth. I guess this means I am permanently a song-and-dance man?

But yeah—I have two books coming, one with a film-performance. They are interwoven projects. The Evening Pink started in 2012. Shock and Awe was coming together as a journal then, the edition hadn’t been made yet. I began to make photographs in the world through performance. These were not controlled. Just weird ideas—go see what happens.

Eventually I figured out this was a Western. Then in 2015 I found a 35mm Silver Nitrate reel off the grid in New Mexico, on the site of an abandoned theatre, itself situated near an abandoned mine. This film—now known as Mickey—seemed lost forever, it was crumbling to dust. But the relative humidity in the Bay saved it. In 2016 I was able to un-reel the film, make a scan, and now I’m printing 16mm reels for performance work. And making a book—which will stand close to The Evening Pink. The film looks likemy work, though it was made in 1918. It’s a bit nuts. Now I just need to nail the performance.

Any artists you’ve just found out about that are exciting to you at the moment?

I am very moved by touring artists. I have been reflecting on musicians a lot these last couple years. The grind. It’s impressive shit. But I hate them, too, because they get paid. 😉

In photography, Sergej Vutuc has really blown my mind. He tours, throws up installations, fast. Books are made constantly. Each one is better than the next. Riso Printing. He performs inside his installations. He is the nicest guy, too.

I cast a wide net, otherwise. Photography—for me—still means all kinds of folks working with cameras, and without. My friends are mostly artists (I’ve never had a crew of photographers), and I think they still influence me the most. People who “walked away” from the Art World. Mickey runs the most successful—and enduring—Social Practice project I’ve ever heard of—of course it’s not in the canon: THE GOSPEL FLAT FARMSTAND! This was all an experiment in outgrowing capitalism. Prove to people they are honest. The whole farm is on the honor system. The art space is powered by kale purchases. Thousands of tiny patrons. This grew out of years of public dinners, bread baking, pizza making, which put together people who would never otherwise meet, hang out, talk, etc.

I’m still waiting for my friend Randall to drop his master piece.

But in Photography-land, I do want to tip my hat to the small press folks, particularly in Europe. It’s mind blowing to see what photography books have become over there. I don’t know how it’s influenced me yet, but I know that when I see an American monograph I just laugh (rather than cry).

When do you feel the most alive and excited to be an artist?

When do you feel the most alive and excited to be an artist?

Breaking the rules. And not for nothing. I’m not trying to be the avant-garde-as-R&D-for-late-capitalism. Ken Kesey’s “Just Walk Away” speech is always in my ears—building anew, not getting trapped in some dialectic of resistance. I’m looking for a middle-class existence, for me, for the folks coming up. Unions, self-determination, the whole nine.

***

Ethan went to visit Coventry University and Professor Gemma-Rose Turnbull, and I asked her if any of her students could speak to the experience. Thomas Tierney told us:

Ethan went to visit Coventry University and Professor Gemma-Rose Turnbull, and I asked her if any of her students could speak to the experience. Thomas Tierney told us:

Talking with Ethan and seeing his work opened up new ideas on what photography as a tool does for me and how in the documentation style in which I shoot doesn’t always have to be perfectly timed photos, it can also be a reflection on oneself. Using others to portray your own personal story can create a unique way of story telling that is also self portraiture. And he’s just an all round awesome guy! HE MADE PIE!

Thank you, Ethan, for sharing your wonderful work with us!

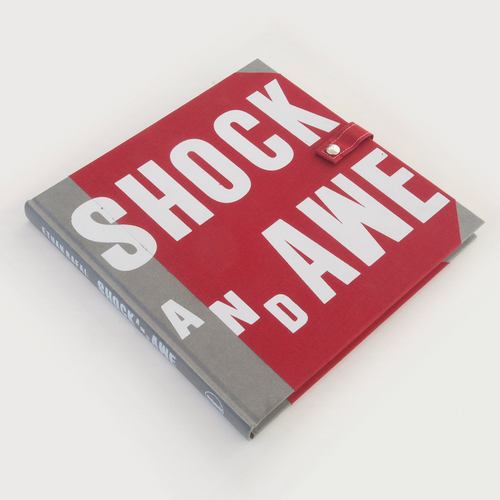

Incidentally, Ethan also just generously donated one of the LAST copies of the first edition of Shock and Awe to Adobe Books in San Francisco. The entire purchase price will go to support arts and culture programming there. Grab it!!